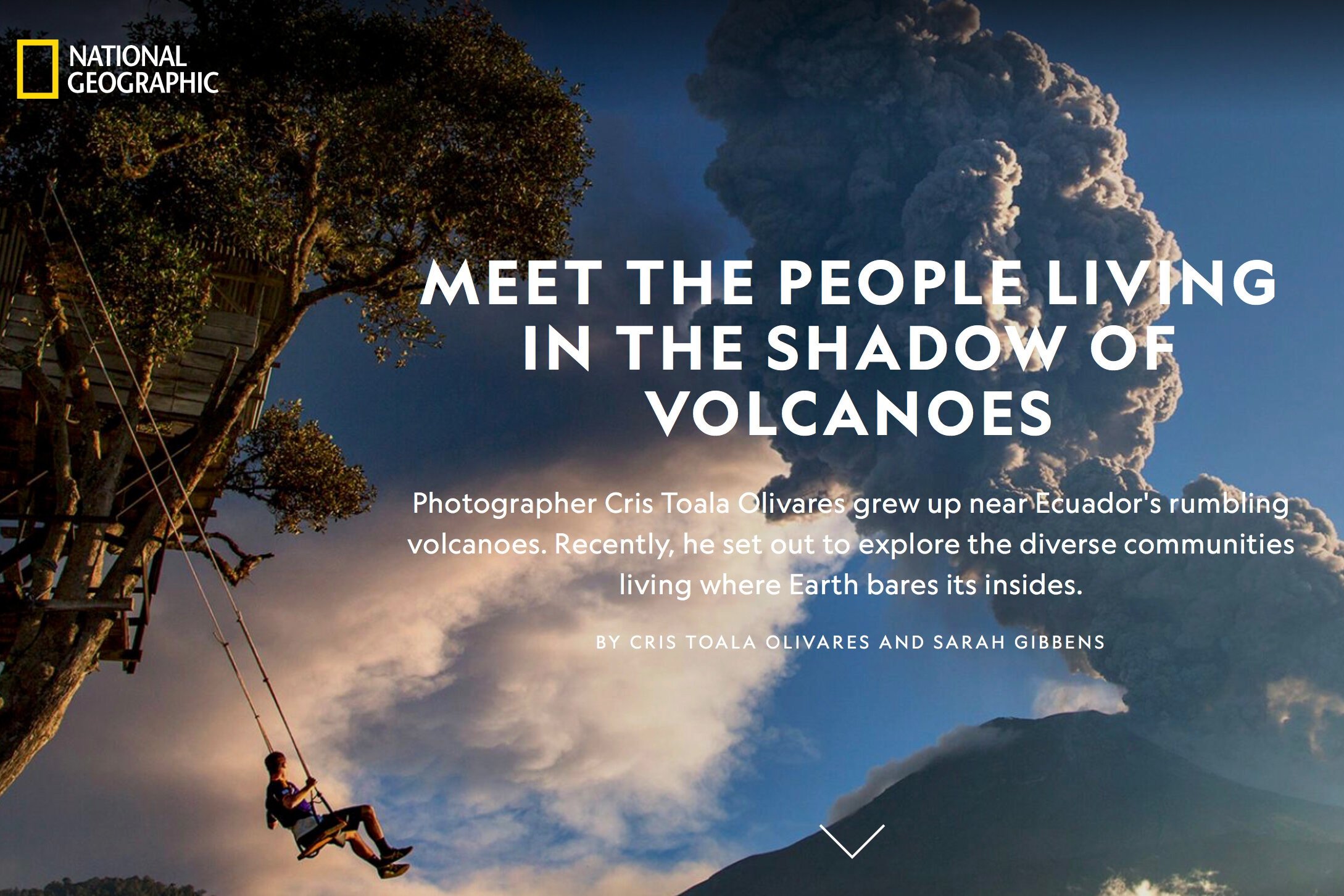

The Living with Volcanoes project began in 2014 when I found myself at the forefront of one of the largest eruptions in my home country, Ecuador. In that moment, one question kept haunting me: why do people live here? This curiosity led me to immerse myself in the lives of communities living near active volcanoes around the world. Through my photography and storytelling, I strive to share and preserve the ancestral wisdom of these people and their unique relationship with nature, offering us valuable lessons on resilience, connection, and survival.

From this journey, the book Living with Volcanoes was born—a project that captured these stories and perspectives. I invite you to explore some of the stories featured in the book and discover the incredible lives of those who call these volcanic landscapes home.

Tungurahua in my native country Ecuador was

the first volcano that became a subject for my pictures, and it inspired my journey around the world. Lying about 130 kilometres south of the capital Quito, its name means “throat of fire” in the indigenous Quechua language, according to some interpretations. In ancient legends, the warriors Cotopaxi and Chimborazo, which are the names of other volcanoes nearby, were rivals for the love of “Mother Tungurahua” as it is known locally.

These are myths that I grew up with in Ecuador and that have always intrigued me. Since 1999, the 5,023-metre Tungurahua has resumed activity, and when I heard it was erupting again in 2014 while

I was on assignment in the country, I knew I had to go to see it.

During the drive over, my colleague and I came to a junction in the road. He said one way would take us to the usual site for journalists to photograph Tungurahua and the other way would take us to “La Casa del Árbol” (The Treehouse), an observation point near Baños set up by local Carlos Sánchez. As I hoped for some beautiful and artistic pictures, I chose the second option

Not long after we reached the treehouse where Sánchez monitors the volcano and has built a swing from which people can view it, a series of eruptions started. We were in the ideal place to see the huge

“pyroclastic” hot ash cloud emerge, but luckily, it was not coming towards us. Instead, it went towards the more common observation site for reporters, though fortunately they had all left by then. I was glad my intuition had led me in the other direction.

After a particularly big explosion, when others

were running away from the treehouse, I stayed and tried to capture some striking angles. I remember feeling alone with my subject, Tungurahua. I was scared but I tried to whisper to the volcano that I just wanted to catch her best side, like a painter might say when trying to depict a person. There was a gentle evening light descending as the ash cloud swirled and I was able to take some fantastic portraits. I think she showed me the reason for her “throat of fire” name.

Unbelievable to see such an eruption, it looked like a bomb that came out of the center of the earth.

During this time in Ecuador, I met several people who lived around Tungurahua, including flower growers and farmers.

I wanted to know why they had made this place their home, and what they were like. They led humble, simple lives, but they were content and close to their land and to the volcano, which they saw as a protective maternal figure.

Sánchez told me many other local legends linked to magic and mythology in the area.

It was this initial experience that convinced me to start travelling the globe to find out more about volcanoes and the people who live near to them.

At that time i was sending pictures of the Tungurahua to the press office i was working for on the spot, when everyone had run away.

I often get into situations where sometimes you have to drive alone and be creative to solve that.

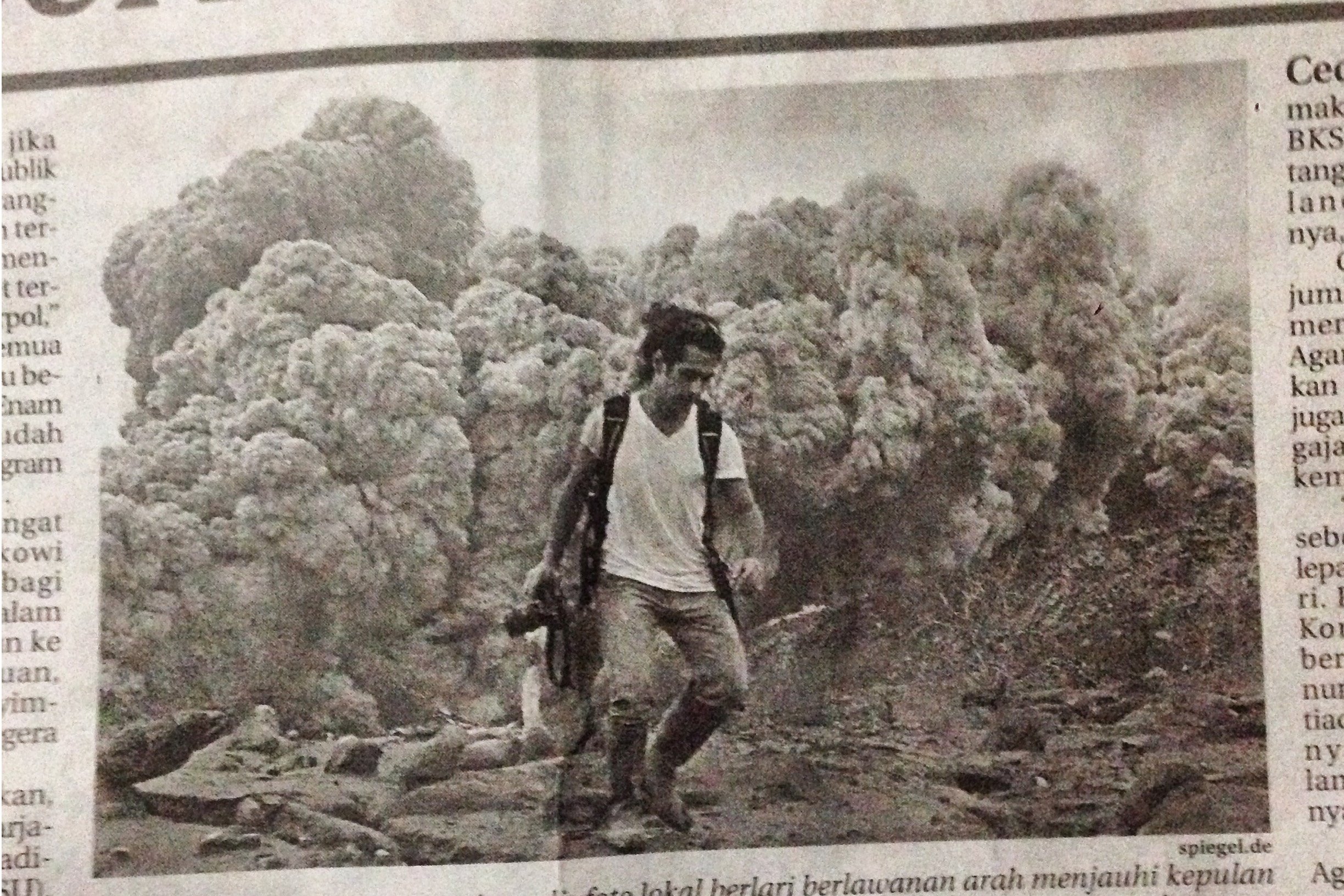

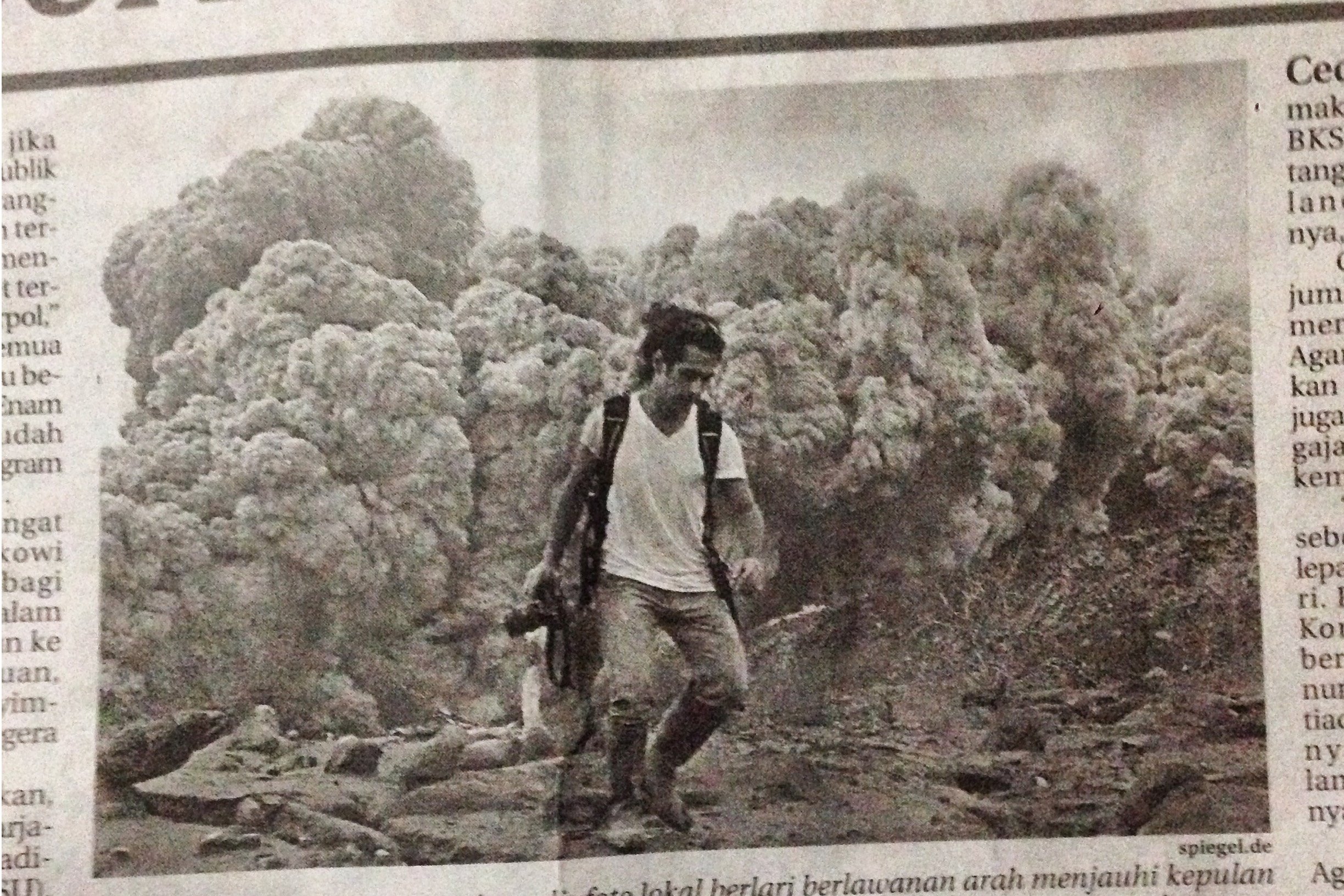

From Ecuador I went to Sinabung Indonesia a month later.

A screenshot of the Tungurahua in the Reuters website

My encounter with Mount Sinabung in North Sumatra, Indonesia, brought me face to face with the extreme and unpredictable violence that can come from a volcano. After lying dormant for about 400 years, it became active again in 2010, forcing thousands of local villagers and farmers to evacuate.

I visited in 2014, when fast-moving pyroclastic flows of rock fragments, ash and hot gases were sweeping through nearby settlements, destroying houses and livelihoods, and killing anyone in their path. Several villages on the flank of the 2,460-metre volcano had been abandoned and left covered in ash.

At the time I was still inexperienced with volcanoes and keen to take some close-up pictures of the destruction. Along with another photographer Sutanta Aditya, I had reached a village high up Mount Sinabung that looked like it had been bombed.

Suddenly, there was a new explosion and we saw a huge cloud of ash coming towards us.

I can remember thinking that I was going to die. We started running and I could feel the heat getting closer.

Many of the inhabitants around Mount Sinabung are farmers. They take the risk to live near to the volcano because they can benefit from the fertile soils in the area, growing rice, maize, tomatoes, chilli, cocoa, coffee, and more.

Since it started erupting again and wreaking havoc for nearby residents, many view this as a sign the volcano is “angry”. They give various explanations for this, stemming from folklore and other beliefs. Among the Muslims in the area, some say people have not been praying enough, others say someone prepared food that is prohibited under Islamic law.

People leave messages to the volcano on stones, asking for a halt to the explosions. “End this suffering, Lord, we are tired, father” was among the written pleas I saw.

Back in 2018 I was featured in TED IDEAS. Volcanoes have a certain hypnotic appeal — but would you want one in your backyard? I introduced you to the humans who co-exist with these unstable and sometimes deadly forces of nature.

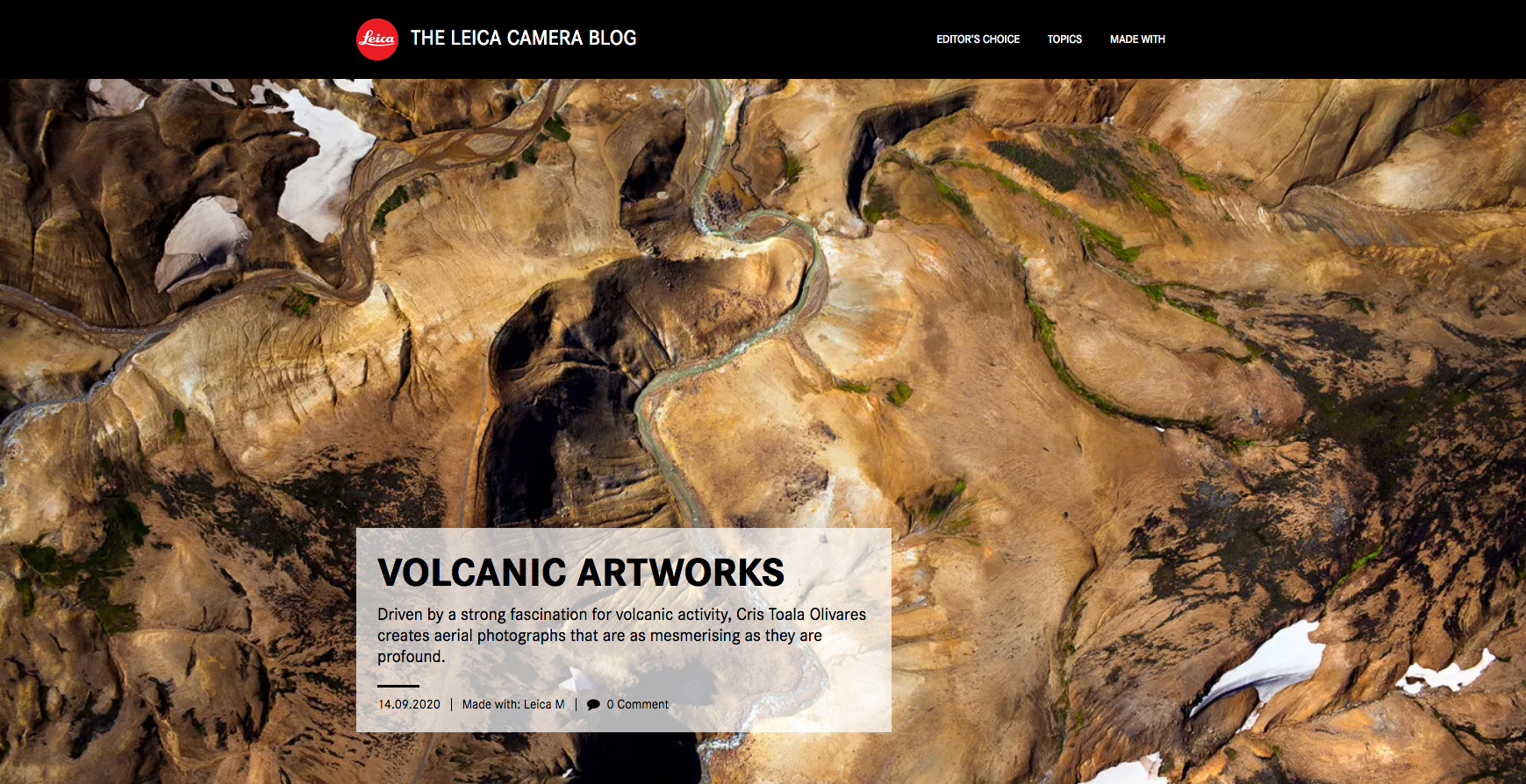

At the end of 2020 I was featured in Leica’s camera-blog. I used their camera’s to create these “volcanic artworks”, as they liked calling them. In this blog I talk about my ongoing project which I have been working on for the past 8 years.

"An important contribution to our understanding of the beautiful but hazardous relationship between humanity and volcanoes. Toala Olivares brings personal insight into the spectacle of our planet in its most violent and primordial state."

—George Steinmetz, National Geographic Explorer and New York Times photographer

Sunrise overlooking the massive destruction the volcano has caused sixteen days after the first erruption, burring the second village of Bangaeira with lava.

Ecuador, Cotopaxi, 2015

Cotopaxi south of Ecuador’s capital Quito, is among the highest and most dangerous active volcanoes in the world, but the legends around it are linked to love. They are based on a rivalry between the warriors Cotopaxi and Chimborazo for the beautiful Tungurahua, which are all names of volcanoes in Ecuador. According to variations of tales in local mythology, Tungurahua married Chimborazo and had a child called Guagua Pichincha, another volcano which looms over the Quito skyline.

As I was born in Ecuador and knew about these legends, I expected to discover examples of deep love, devotion and mythical belief in the people living around Cotopaxi. Stories are also told here of the major eruption in 1877, passed down through generations. I visited during the recent eruption of ash and steam in 2015, when the local people saw their giant 5,897-metre (over 19,000 ft) neighbour wake up again.

I was with Segundo Benites, a cattle farmer who was among the last people to leave the area of Mulalo, at the foot of Cotopaxi , on his last days as he prepared to go to Quito. Tears were falling down his face as he explained his connection to his land, the beauty of the mountain and his surroundings, and the sense he had that Cotopaxi was throwing him out. He said he knew he had to leave eventually but something was keeping him there, because he was so deeply rooted in the area. Committing himself to this land had been linked to a duty to his mother and relatives to stay there after his father died. The significance of family here also extended to the snowcapped volcano, who the local people referred to as Daddy Cotopaxi. They were saddened that they were having to leave him but also accepting of his anger, because of the respect that they had for him.